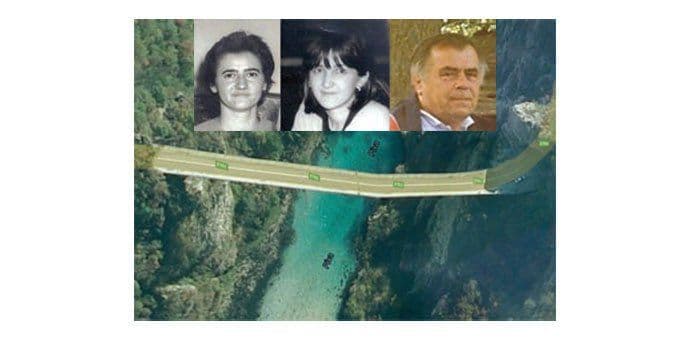

WAR CRIME TRIAL POSTPONED

22/06/2022

JUSTICE ELUSIVE AFTER 30 YEARS FOR KLAPUH FAMILY

06/07/2022INTERNATIONAL DAY IN SUPPORT OF VICTIMS OF TORTURE: STOP TOLERANCE OF STATE VIOLENCE

Photo: European External Action Service / CC BY

(“He whose law is written by his cudgel leaves behind stench of inhumanity.” – Petar II Petrović Njegoš)

On the occasion of the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, which the United Nations celebrates on June 26 each year, Human Rights Action (HRA) highlights that Montenegro still does not respect the ban on torture and other ill-treatment in line with international standards. Investigations are often ineffective, especially for the most serious forms of ill-treatment, which creates the impression of impunity and encourages such acts to be repeated. An extremely mild penal policy also contributes to this, so suspended sentences are also imposed for torture followed by severe bodily injuries. The police and the prison system continue to employ those officers whose responsibility for torture has been established by the court, as well as many others who have not been prosecuted and who have carried out or supported the ill-treatment. The new leadership in the police, the state prosecutor’s office and the new forces in the higher courts must change the current tolerant attitude of the state towards civil servants who ill-treatment people.

In May this year, the UN Committee against Torture expressed Montenegro’s concern about reports of physical and psychological torture of persons deprived of their liberty by the police, during their interrogation, in order to extort testimony or obtain information, and the lack of effective investigations.

The main disadvantage of ill-treatment investigations is that they are not conducted urgently and thoroughly enough and they last too long. With the exception of the beating of Miodrag Martinović, which was only partially prosecuted and punished, other cases from the October 2015 protests are still unprocessed after six years and are in the reconnaissance phase, as are the cases from the 2020 protests in Nikšić and Budva, cases on reports of extortion of testimonies in the Podgorica police from 2020 and 2021 and cases related to the actions of the police in Cetinje from September 2021.

Detaining the case for a longer period in the reconnaissance phase allows police officers who ill-treatment citizens to remain in official positions, as the law still does not provide for the obligation to suspend them at this stage of the proceedings. This practice is contrary to international standards and jeopardize the administration of justice.

In 2020-2021 at least 19 people filed serious reports of extortion of testimonies through brutal ill-treatment, mostly related to the actions of criminal inspectors in the Security Center (SC) of Podgorica and officers of the Sector for the Fight against Organized Crime and Corruption. So far, only in the cases of the injured parties Marko Boljevic and Benjamin Mugosa, the state prosecutor’s office has accused a total of five police inspectors (Danilo Grbovic, Dalibor Ljekocevic – in both cases, Bojan Vujacic, Ivan Perunicic and Nemanja Vujosevic) of extortion testimonies in May 2020. No one has yet been charged with torturing Jovan Grujicic in order to extort testimony, followed by his forced removal from treatment and denial of therapy.

Last year, the Constitutional Court adopted the constitutional complaint of Braslav Borozan and determined that the State Prosecutor’s Office did not effectively investigate the torture of him in the premises of the SC of Podgorica in 2015. He explained the conclusion by the failure to act urgently on the report against the police officers, since it took the state prosecutor three and a half years to decide on it. Paradoxically, it took the Constitutional Court three years to reach a decision in this case, although it had grounds to give priority to the case.

The UN Committee against Torture also criticized Montenegro’s lenient penal policy, the low penalties prescribed by the Criminal Code for ill-treatment and torture, and the fact that these acts are obsolete. Suspended sentence is the rule in Montenegro for this type of crime. For example, for the torture of prisoners in conjunction with serious bodily injury from 2015, prison guards in Podgorica were sentenced in 2020 by the High Court in Podgorica to only suspended sentences, contrary to the international standard. The highest sentence for torture in conjunction with grievous bodily harm ever imposed in Montenegro is in fact the minimum sentence for both offenses, a total of one year and five months in prison, handed down to two former Special Anti-terrorist Unit members, Goran Zejak and Boro Grgurovic, for brutally beating Martinovic in 2015. Otherwise, the range of punishment for torture by officials is from one to eight years, and for grievous bodily harm from six months to five years.

Last year (2021), the European Court of Human Rights unanimously determined in the case of Momcilo Baranin and Branimir Vukcevic that the state prosecutor’s office did not provide an effective investigation into their police ill-treatment in Zlatarska Street during the October 2015 protests. In the Martinovic case, a three-judge panel, including a Montenegrin judge, rejected the application, finding that Martinovic had lost “victim status” because the Constitutional Court of Montenegro had found a violation of his rights due to failure to conduct an effective investigation, he received compensation, two perpetrators were punished, who reported themselves, and their commander (who assisted them after the commission of the crime) was sentenced.

Although Montenegro has a law to compensate victims of torture, its implementation has been unjustifiably delayed until the date of Montenegro’s accession to the European Union, which is quite uncertain. Also, the Law on Free Legal Aid still does not cover victims of police torture, while police officers accused of torture are provided with free legal aid.

The state must provide serious protection against the ill-treatment of all people in its territory, primarily when the ill-treatment comes from officials. Such protection includes effective investigation, effective prosecution, and appropriate punishment and compensation for victims. Those who are responsible for ill-treatment cannot be part of the state apparatus. “He whose law is written by his cudgel leaves behind stench of inhumanity” Njegoš wrote in the Mountain Wreath back in 1846.

English

English