PARENTS RECOGNIZE CIVIC EDUCATION AS KEY TO A BETTER SOCIETY AND LESS VIOLENCE

30/07/2025

Number 10: Judicial Monitor – Monitoring and Reporting on Judicial Reforms

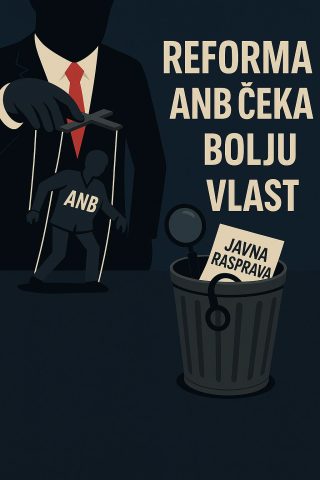

01/08/202521 NGOs APPEAL TO THE GOVERNMENT AND MPs: TAKE THE OPPORTUNITY TO REFORM THE NATIONAL SECURITY AGENCY

Once again, we urge the members of parliament to halt any further decision-making on the Draft Law concerning the National Security Agency (NSA). It is essential to create space for a broad and inclusive public discussion that considers the views of relevant experts, organizations, and institutions. Without democratic oversight of security services, Montenegro cannot ensure legal security nor a path toward a European future.

Non-governmental organizations regret to highlight that, after decades of advocating for the reform of the National Security Agency, the current government has yet to propose a law that would establish a modern, professional, and democratically controlled security service.

Should such a law be adopted at this time, Montenegro will miss a crucial opportunity to create a service that prioritizes the interests of citizens over those of political elites. This would further endanger the processes of democratization, rule of law, and European integration.

The draft law on the NSA, which parliamentarians are set to decide on today, was developed in secrecy, lacking public discourse, thorough analysis of its impact on human rights, and alignment with international treaties and the legal framework of the European Union (EU). This is particularly concerning as Montenegro is currently in a decisive phase of EU accession. By proceeding with its adoption, the government would be effectively rejecting the offer of the European Commission to assist in improving the text of the law, without justification. This is not the approach of a government committed to fostering democratic reforms; rather, it reflects an intention to consolidate power, viewing the secret police as a crucial asset in that pursuit.

The urgency in adopting the Draft Law appears driven by a goal to dismiss employees who were hired under the previous administration before the mandatory retirement deadline. This would enable the replacement of these individuals—without public competition or merit-based testing—by those deemed loyal to the new authorities. Additionally, another objective seems to be the exemption of the NSA from the public procurement system.

Furthermore, there has been an attempt to weaken the already limited guarantees for privacy protection against potential abuses by the secret service.

Restoring trust in an agency historically marred by accusations of power abuse and insufficient oversight—whose former director is currently facing trial for unauthorized surveillance of numerous public figures—will fall upon a future government that possesses the democratic capacity necessary to guide the country toward European Union accession.

Entrusting such extensive powers to a service that has never undergone meaningful reform raises serious concerns, especially as the public remains uninformed about who has been held accountable for past abuses and through what processes. There is a troubling intention to narrow the scope for civic oversight, transforming the institution into a potentially dangerous tool for political manipulation.

Thanks to the prompt intervention of non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the Government was alerted to the fact that the Draft Law undermines existing privacy guarantees rather than enhancing them in accordance with the recommendations from the United Nations Human Rights Committee.

In the wake of discussions within the Security and Defence Committee, the Government proposed amendments that largely preserved the status quo. Some judicial oversight was instituted over the surveillance activities targeting the information and communication systems of state administration bodies and legal entities with public authority (such as the Pension and Disability Insurance Fund and the Health Insurance Fund). Additionally, judicial control was applied to two other new competencies of the NSA—surveillance of international communications and inspection of premises, vehicles, and objects—which had already been outlined in the Draft Law.

Regrettably, existing privacy guarantees have not been improved. For instance, the law fails to provide for judicial oversight regarding the determination of electronic communication users’ locations, even though the Constitutional Court has established that this falls within the realm of privacy protection. Furthermore, the recommendation from the Human Rights Committee to introduce judicial oversight concerning access to databases held by legal entities, such as banks and NGOs, was not accepted.

The arguments presented by the drafters—claiming that judicial oversight of data access would impede the NSA’s operational effectiveness and burden the courts—do not sufficiently justify the lack of guarantees for the protection of human rights. Independent oversight and judicial protection are foundational elements of a professional and democratic security service.

Although the complete exclusion of public competition in the hiring process was avoided, this alone does not guarantee a transparent, merit-based recruitment process.

Under the provisions of the NSA Law, NSA officers—who engage with the broadly defined concept of “national security” and are not mandated to possess legal training—are afforded greater powers than those granted to state prosecutors and police officers during preliminary investigations of clearly defined criminal offenses. This is disproportionate and contradicts international standards designed to protect the right to privacy.

The law fails to establish a requirement for the destruction of data that is deemed unnecessary after collection, or that was gathered without justification. This deficiency paves the way for the prolonged and unjustified retention of sensitive personal information, lacking a solid legal foundation.

Alarmingly, the exemption of the NSA from the public procurement system, coupled with the removal of the obligation for regular reporting to other state authorities, significantly diminishes the potential for institutional oversight and heightens the risk of abuse.

The absence of a public consultation process has stifled opportunities for interventions that could clarify the scope of the NSA’s activities, undermining efforts to promote good governance and foster a culture rooted in the rule of law.

Moreover, the vague notion of “national security interest” should not be invoked as a rationale for diminishing human rights guarantees or bypassing the principles of accountable public administration.

In contrast, genuine security is synonymous with the rule of law, the protection of human rights, and the establishment of effective democratic oversight over the operations of security services.

English

English