02/05/2012 ON THE OCASSION OF THE WORLD PRESS FREEDOM DAY

03/05/201222/ 06/ 2012 Monitoring report “Respect for Human Rights of Detainees and Prisoners in the Institution for Execution of Criminal Sanctions”

02/07/201228/ 05/ 2012 Twentieth Anniversary of the 1992 Montenegro Deportation Crime against Bosnian Muslim Refugees – Justice is Still Far Away

It will be twenty years this May since a crime against Bosnia-Herzegovina Moslem refugees was committed in Montenegro, a crime colloquially known as the “refugee deportation crime”. Montenegrin civil servants systematically arrested them in 1992 and handed them over to Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic’s armed forces to use them as hostages and exchange them for captured Serb soldiers. Most of the deported refugees were immediately executed, while several were tortured in the camps and ultimately exchanged. The graves and execution sites of some of the victims of this crime are still unknown. What is known is that all of them were civilians who had sought shelter in Montenegro from war, that there were no legal grounds for their arrests and that their deportation was organised and effected mostly via the police station in Herceg Novi.

Sixteen years after the crime, after a four-year lawsuit, Montenegro agreed to a settlement and paid over four million Euros in damages to eight surviving victims and 200 members of 42 families whose loved ones were killed. This is an unprecedented illustration of collective reparations for victims in this beleaguered region and one of the rare shining examples of collective reparations in the world. The damaged parties’ success can partly be attributed to the intense interest of international organisations in their case and the unrelenting attention Montenegrin media, eminent representatives of civil society and specific political parties have been drawing to it.

On the other hand, it remains unknown who is to blame for this crime even now, twenty years later. The then Montenegrin President Momir Bulatovic explained that a “state’s mistake” was at issue, which leads to the conclusion that the “state” i.e. its tax-payers should atone for it, although many of them were not in any position to take decisions about this crime or even vote for those who were. What is even more unpleasant is that the Montenegrin court is still unclear about whether this was a war crime at all. In my opinion, elaborated in the upheld appeal of the first-instance judgment filed by the mothers of two victims, the court is still mostly at odds with international humanitarian law, which it needs to apply in this case.

Judging by the indictment, the Montenegrin prosecution office has realised that a war crime against civilians was at issue here, but only because of their “illegal resettlement”, as if they had been resettled to a beautiful place albeit despite their will, not to the Foca death camp, as the ICTY also established. The problem with the Montenegrin prosecution office is its continued involvement in the very crime, for which it gave the green light to the police, as state documents and Momir Bulatovic testify. The chief prosecutor at the time, Vladimir Susovic, is still a member of the Montenegrin Prosecutorial Council. The state prosecution office’s view on this crime thus reflects its historical role in it. Supreme State Prosecutor Vesna Medenica did not proudly announce the launch of the investigation in 2005 at a news conference, but at the first hearing, when she spoke in defence of the state from the victims’ reparation claims. The motion to launch the investigation included the prosecutor’s suggestion to question 15 deceased people as witnesses. Only after the settlement, in January 2009, did the prosecutor charge nine civil servants, most of whom held lower ranks, with the exception of the then chief of state security and an assistant police minister. The command responsibility of the then state leadership, the Prime Minister Milo Djukanovic and President Momir Bulatovic, who were receiving the state security bulletins ex officio, and had to have known about all the arrests in Montenegro during that war period, was not investigated.

Not everyone, who can justifiably be presumed to be responsible, has been indicted, while the individual indictments are based on imprecise and insufficiently serious grounds. Even the names of all the victims are not listed. The parts of the puzzle are inserted only to the extent necessary to prolong the matter indefinitely.

The first act of the trial ended with an unbelievable judgment, in which the court concluded that the indicted civil servants could not have committed a war crime because the then Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which Montenegro had been part of, had not declared a war against Bosnia-Herzegovina! As if international law allows a state not to declare war and then proceed to freely commit crimes and let the statute of limitations expire. As if it is enough to be ingenious, not declare war and avoid responsibility for such horrible and tragic events. The judgment rightly provoked doubts about political influence, because, had it stuck, not only the indictees, but all others who may be linked with this crime as well would have been acquitted of responsibility.

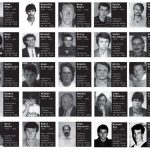

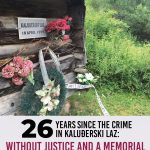

And finally, twenty years later, Montenegro does not have even a Remembrance Day or a monument to the 42 dead victims of this crime we certainly know of. Their faces will look at us again this year from posters published to mark one of the previous anniversaries. Justice has formally not been served. Nor is it likely that it will be. Proceedings that could have served as convincing evidence of the rule of law in Montenegro are turned into a scandal day in and day out; the victims were pushed into the same, nameless grave. This is the way to sow confusion and relativise crime. This is not the way to prevent our children and grandchildren falling tomorrow as victims because of their names or faiths.

Tea Gorjanc-Prelević, HRA executive director

Published in Daily Vijesti on 26th May 2012

English

English