NO DIALOGUE, ONLY PUNISHMENTS: PREVENT THE DRACONIAN BAN ON ROAD PROTESTS

17/07/2025

SLOBODAN PEKOVIĆ CONVICTED FOR CIVILIAN MURDERS AND RAPE IN FOČA IN 1992 – MONTENEGRO’S FIRST VERDICT FOR WARTIME SEXUAL VIOLENCE OFFERS HOPE TO VICTIMS

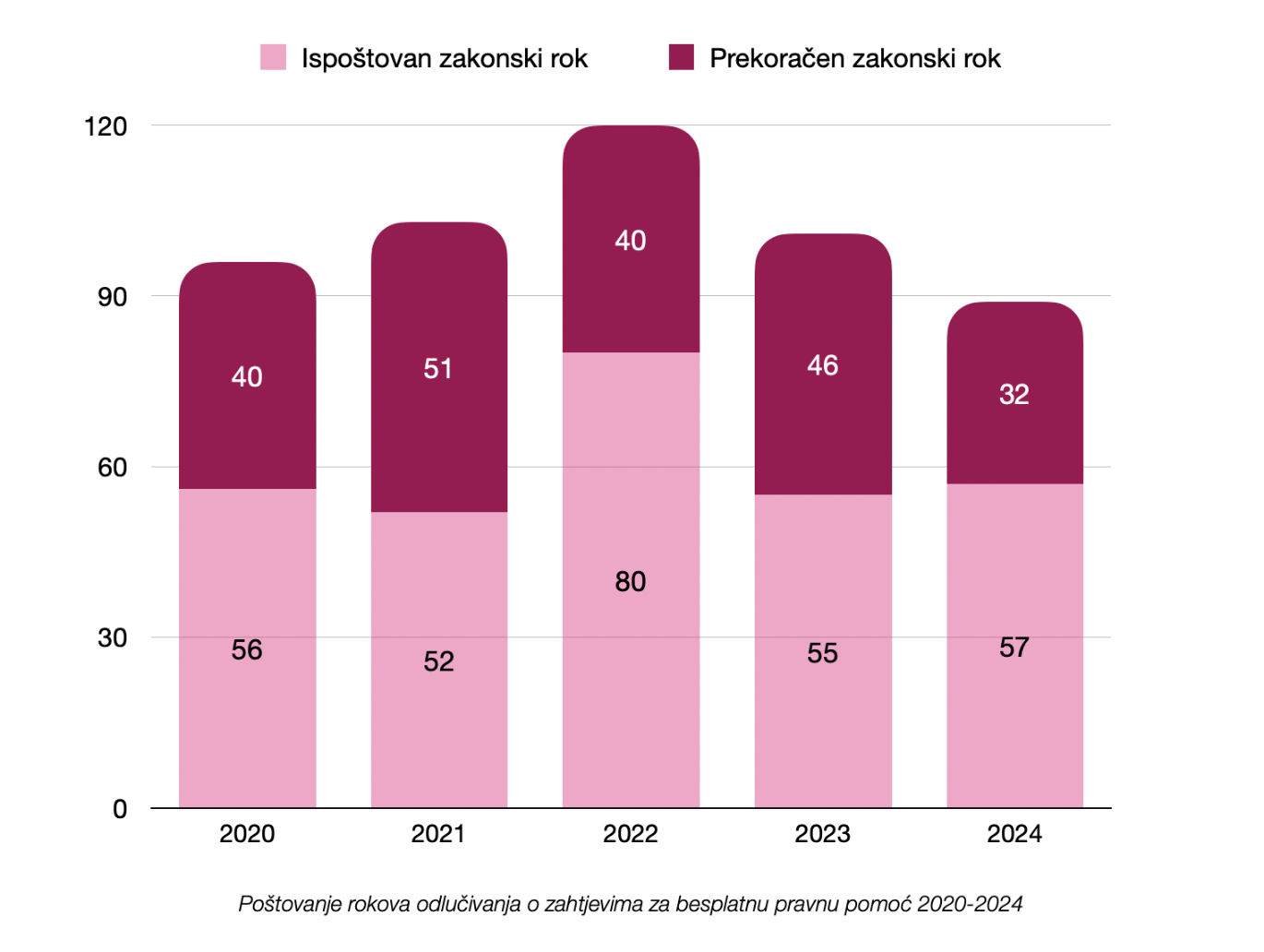

21/07/2025CIN-CG/HRA: MONTENEGRO IMPROVED THE LAW ON FREE LEGAL AID LAST YEAR, BUT STILL DOES NOT IMPLEMENT IT PROPERLY – Relatives of those who went missing during the war should also be allowed to use free legal aid

“A judge in Danilovgrad told me I shouldn’t be concerned about who my lawyer is. I haven’t received any updates on the case for five months now—I’m only told ‘you will be called’. I’m really disappointed; everything is moving far too slowly…,” said one of the 13 interviewed users of free legal aid (FLA), sharing her experience with the Center for Investigative Journalism of Montenegro and Human Rights Action (CIN-CG/HRA). She explained that she still hasn’t met her lawyer and doesn’t even know who is representing her in the proceedings following her report of domestic violence.

Free legal aid is available to individuals with low income, but also to all victims of torture, domestic violence, children without parental care, persons with disabilities, and others. Amendments to the Law on Free Legal Aid passed last year introduced a specialized approach to providing legal support to particularly vulnerable groups. Victims of torture and criminal offenses against sexual freedom, as well as children involved in proceedings for the protection of their rights, were granted access to free legal aid regardless of their financial status. The scope and types of legal actions available through this form of aid were also expanded.

However, the HRA report “Free Legal Aid in Montenegro: Progress, Challenges and Recommendations” points out that even with the latest amendments, relatives of persons who went missing during armed conflicts have not been recognized as a specific category of beneficiaries, despite the recommendation from the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances from 2018.

“It is stipulated that in proceedings involving children, victims of domestic violence and victims of criminal offenses against sexual freedom, only lawyers with three years of experience in legal practice and who have completed specialized training at the Center for Judicial and Prosecutorial Training may be engaged,” the HRA report states. The report was recently presented at a conference organized by the NGO.

Margaret Satterthwaite, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers

The HRA report also addresses the implementation of recommendations made by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Margaret Satterthwaite, in her 2024 report to Montenegro, issued shortly before the legal amendments came into force.

Satterthwaite recommended, among other things, mandatory specialization of lawyers for sensitive cases—particularly those involving victims of domestic or intimate partner violence—the establishment of oversight mechanisms and professional standards in the provision of free legal aid in cooperation with the Bar Association, and the suspension of lawyers from the list of legal aid providers if they fail to meet prescribed standards.

“Although the law explicitly provides for the creation of special lists of lawyers for specialized representation of victims of violence, human trafficking, criminal offenses against sexual freedom, and children, this legal obligation has not yet been implemented in practice. Courts still rely on the unified list of the Bar Association, which includes all lawyers interested in providing free legal aid, without any record of their specialized knowledge,” the HRA report concludes.

Based on statements from free legal aid users as well as experts at the conference, the legal amendments and many of Satterthwaite’s recommendations have yet to be fulfilled.

According to users’ experiences, the appointed lawyers in most cases delay proceedings or are not sensitized or familiar with the cases they are supposed to handle.

However, the HRA report also shows that the number of requests to replace assigned lawyers is very low—only 1.25 percent—and that problems in communication with lawyers are rarely reported to the services responsible for free legal aid (FLA) in basic courts.

Most of the interviewed FLA users said they hesitate to request a change of lawyer because they don’t know which lawyers are good, or they hope they will still receive at least some form of assistance, given that they cannot afford to pay a lawyer themselves.

NGOs to be involved in providing free legal aid; torture victims to be covered by specialization

The HRA report recalls the recommendations of the UN Special Rapporteur and, among other things, recommends mandatory specialization of lawyers for representing victims of torture, clarifying oversight mechanisms for the provision of free FLA, possible suspension of lawyers in particularly sensitive cases, and easing eligibility criteria for individuals in difficult financial situations.

During the panel, Satterthwaite emphasized that it would be important for NGOs to participate in providing FLA, as this has proven to be good practice in many countries. One of her recommendations—shared by many human rights organizations but not accepted in the recent amendments to the Law—was for the state to allow NGOs to provide FLA.

“NGOs are often the first point of contact for people in need of legal support, especially among vulnerable and marginalized groups, including victims of violence, persons deprived of liberty, asylum seekers, Roma, persons with disabilities and others. In that sense, beyond increasing the geographic and thematic availability of services—particularly in areas where state institutions are absent or hard to access—this measure would allow for a higher level of specialization and quality in the provision of legal aid, thanks to the expertise and long-standing experience of NGOs in working with particularly vulnerable clients,” the HRA report states.

The UN Special Rapporteur stressed that lawyer specialization is also crucial in these cases, as is accountability for the quality of assistance provided.

“I’ve noticed that lawyers trained to work with trauma survivors feel a sense of pride in that role. Such training should be made available to all, because you never know when a lawyer might have to represent a traumatized victim, even outside of the FLA system. The training should be organized in cooperation with specialized NGOs and should include trauma survivors themselves sharing their experiences, as first-hand learning is invaluable.”

She also emphasized the importance of gathering data on how many lawyers decline FLA appointments, and establishing clear criteria for removing lawyers from the list.

Bojana Malović, HRA

Bojana Malović from HRA confirmed that in practice, the specialization of lawyers for such cases has not yet been implemented. “Its application is expected to begin in early 2026, but it is certainly a shortcoming that victims of torture are not included in the specialization,” Malović explained.

She also added that it is concerning that courts are not respecting their legal obligation to request the removal of lawyers from the list if they are not performing their duties properly. “There were nine approved requests for a change of lawyer due to dissatisfaction with the provided service, but not a single one was forwarded to the Bar Association,” she emphasized.

Željka Jovović, President of the Basic Court in Podgorica, and Aleksandar Đurišić, Vice President of the Bar Association

The President of the Basic Court in Podgorica, Željka Jovović, emphasized that parties often assess the work of lawyers subjectively, and that in most cases, their criticism is not based on an objective evaluation of the lawyer’s performance. Nevertheless, she stressed that measures should be applied to those who do not perform their duties properly. “I insist on removing lawyers who are unwilling to provide free legal aid,” Jovović stated.

The need to update the list of lawyers providing free legal aid is also supported by the Vice President of the Bar Association, Aleksandar Đurišić, who expressed concern over the testimonies of dissatisfied clients. “We compiled the list of lawyers believing that only those who are genuinely motivated would sign up,” Đurišić explained.

Some of the users would have liked to be able to choose their own lawyer through FLA, but all agree that it should not simply be the first person on the Bar Association’s list, but someone who is specialized and who would show greater sensitivity in such cases.

Veselin Radulović, lawyer

Lawyer Veselin Radulović reminded that the essence of free legal aid is for the injured parties to receive quality legal protection. However, he warned of potential abuses if users of free legal aid were allowed to choose their own lawyers, as has happened in cases where defendants selected court-appointed lawyers. “Some colleagues instructed clients to cancel their powers of attorney so they wouldn’t have to pay them personally, and then directed them to choose those same lawyers as court-appointed attorneys,” Radulović explained.

The HRA report points to similar problems, noting that courts have reported defendants requesting only prominent lawyers who were often unavailable or unwilling to take on additional cases, causing delays and the need for reappointments. “A similar dynamic in the free legal aid system would undermine its efficiency and fairness, especially if ‘popular’ lawyers became overloaded while others remained insufficiently engaged,” stated the Basic Court in Bar.

Inappropriate Comments, Delays in Proceedings and Requests for Money

Most of the interviewed women received legal aid after reporting domestic violence, but several stated that when they spoke with their assigned lawyers, the lawyers made inappropriate remarks—such as, “You shouldn’t be like that, after all, he’s a man; you talk too much…”

Some women have not been able to meet with their lawyer for months, while the lawyer delays drafting the lawsuit or criminal complaint. One woman even claims that her lawyer asked her for money. Out of the 13 women interviewed, only four said they were satisfied with the lawyer assigned to them.

One woman, whose child is a victim of peer violence, said she was assigned a lawyer in April, but he still hasn’t drafted the lawsuit or met with her. She expected the lawyer to be knowledgeable and experienced in handling such cases, but so far, all she has received from him is an attempt to persuade her not to sue.

“I told him that his job is to draft the lawsuit and to call me in so we can meet, but that hasn’t happened yet,” she emphasized.

According to the report from the Judicial Council (JC) for last year, out of 2,865 criminal and misdemeanor proceedings for acts of domestic violence, only 114 victims requested free legal aid (FLA)—which is just 3.9 percent.

Maja Raičević, Director of the Women’s Rights Centre (WRC)

Maja Raičević, Director of the Women’s Rights Centre (WRC), emphasized that more victims of violence turn to their organization than to the courts, which may indicate a higher level of trust. She explained that the WRC has spent years developing a “one-stop shop” system, where clients receive all types of services in one place – from legal and psychological support to accompaniment as a trusted person and assistance in communicating with institutions.

“At the Center, we have three lawyers (two women and one man) who provide free legal aid. They are specialized and have been trained for years to work with victims of violence. When we organized the first specialized training for lawyers more than 10 years ago, around 40 lawyers participated, but only two female lawyers stood out afterward as having enough sensitivity and motivation to represent victims. Simply put, these issues cannot be handled by people who hold misogynistic and patriarchal views toward women. Attitudes are crucial when it comes to providing quality free legal aid and understanding the position and rights of victims,” Raičević emphasized.

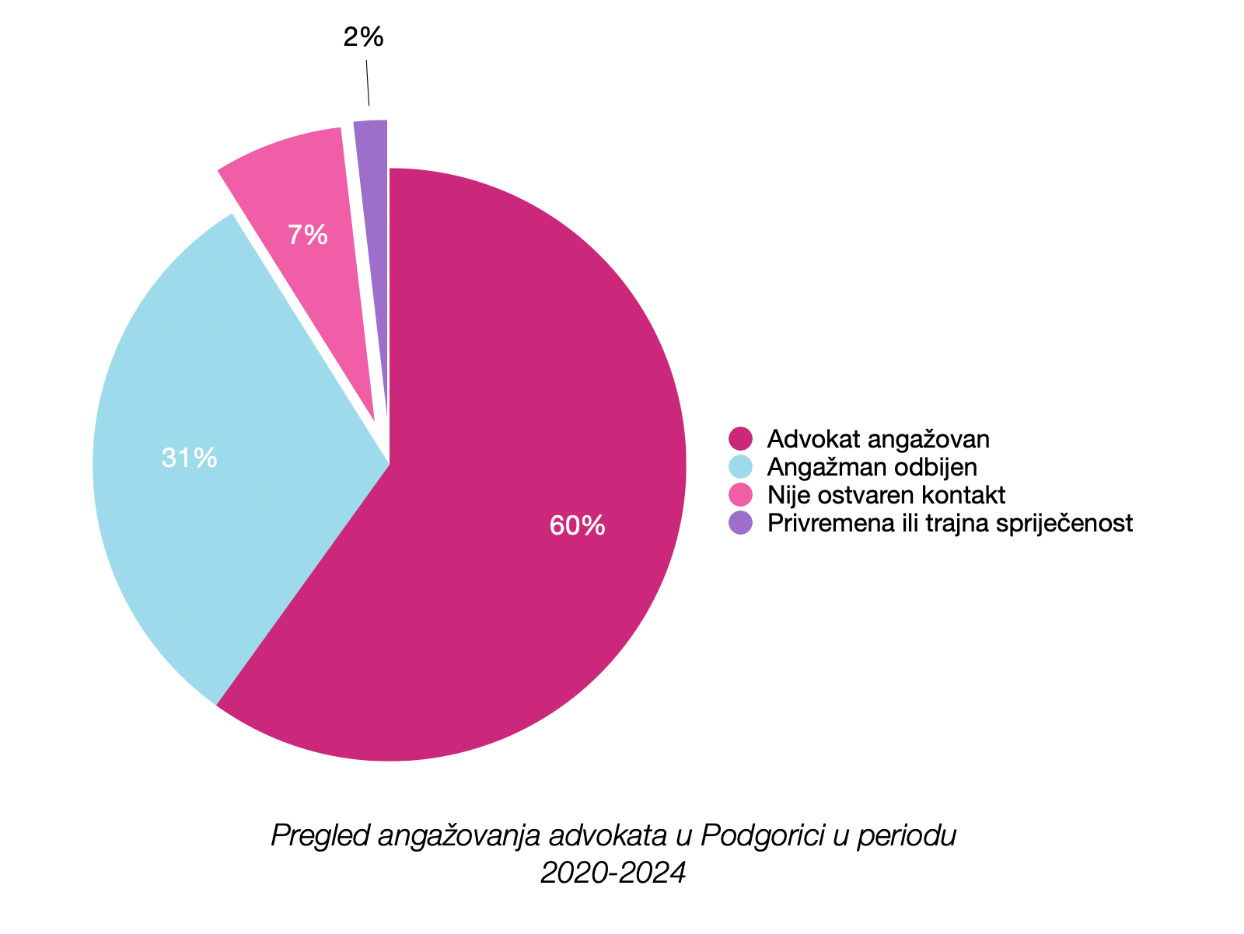

The President of the Basic Court in Podgorica, Željka Jovović, points to the low number of requests for free legal aid, as well as issues with engaging lawyers. She explains that the court staff already knows which lawyers typically refuse to take on free legal aid cases, but despite this, they are still required to contact them due to regulations. This creates additional complications, because when there is a one-hour deadline to decide on a request, and you have to call around ten lawyers who you already know will decline the case, the process is unnecessarily delayed. For this reason, Jovović believes it would be beneficial to revise the list of lawyers and leave only those who are genuinely willing to provide this type of legal assistance.

Raičević also believes that not all lawyers should be included on the list for FLA, but only those who truly have the knowledge and sensitivity for these issues.

“Victims should not be expected to request a change of lawyer. Oversight of lawyers’ work must be effective, but without exposing victims to additional procedures and stress,” she stated.

Mira Saveljić, Executive Director of the Women’s Safe House

Mira Saveljić from the Women’s Safe House added that the list of lawyers must be reviewed as soon as possible, noting that many of them refuse to handle domestic violence cases.

Both representatives of women’s organizations confirmed that they have had clients receiving free legal aid who claimed that their lawyers asked them for money for services that are supposed to be paid by the state.

This is also confirmed by one of the interviewed users of free legal aid, who reported domestic violence. She stated that the assigned lawyer first told her he doesn’t handle criminal cases, and later asked her for money.

“I contacted the Free Legal Aid Service, but he continued to ask me for money,” she claimed.

They Learn About Free Legal Aid Through Friends, Not Authorities

Out of nine women who reported domestic violence, six said they were not informed by the police that they had the right to FLA. A user from Ulcinj claims she only found out about this right during the trial.

Furthermore, most of them were not informed about their right to FLA in related proceedings that often follow after reporting violence, such as divorce, property division, or failure to pay support, once they receive a final court ruling confirming they were victims of domestic violence.

One user emphasized that no one explained to her that the police report alone is sufficient for filing a request for FLA.

Lawyer Đurišić suggested that detailed information about FLA should be prominently displayed in every police department so that users are informed in a timely manner.

On the positive side, nearly all interviewed women praised the court staff and were relatively satisfied with the speed at which they were assigned a lawyer. One user mentioned that it would be good to have more employees in the Free Legal Aid Service in Podgorica.

Eight of them requested free legal aid at the Basic Court in Podgorica, one in Kotor, two in Pljevlja, and two in Ulcinj.

Since these are social cases involving oncology patients, persons with disabilities, or victims of violence, the general impression is that the aid procedures should be more efficient and that communication between courts, lawyers, and FLA users needs to improve, one of the conclusions from the HRA conference.

One recommendation is to ensure that all police officers provide information about the right to free legal aid at the first encounter with victims of domestic and family violence, torture victims, and children.

It remains to be seen whether the system will truly provide quality access to justice for legal aid users, especially for vulnerable and marginalized groups.

Author: Maja Boričić

English

English