FROM THE PANEL DISCUSSION “FACING THE PAST – ACHIEVEMENTS AND CHALLENGES” IT WAS STATED: AN UNRESOLVED CRIME REPEATS ITSELF

27/02/2024

NINE MONTHS WITHOUT A WAR CRIME HEARING

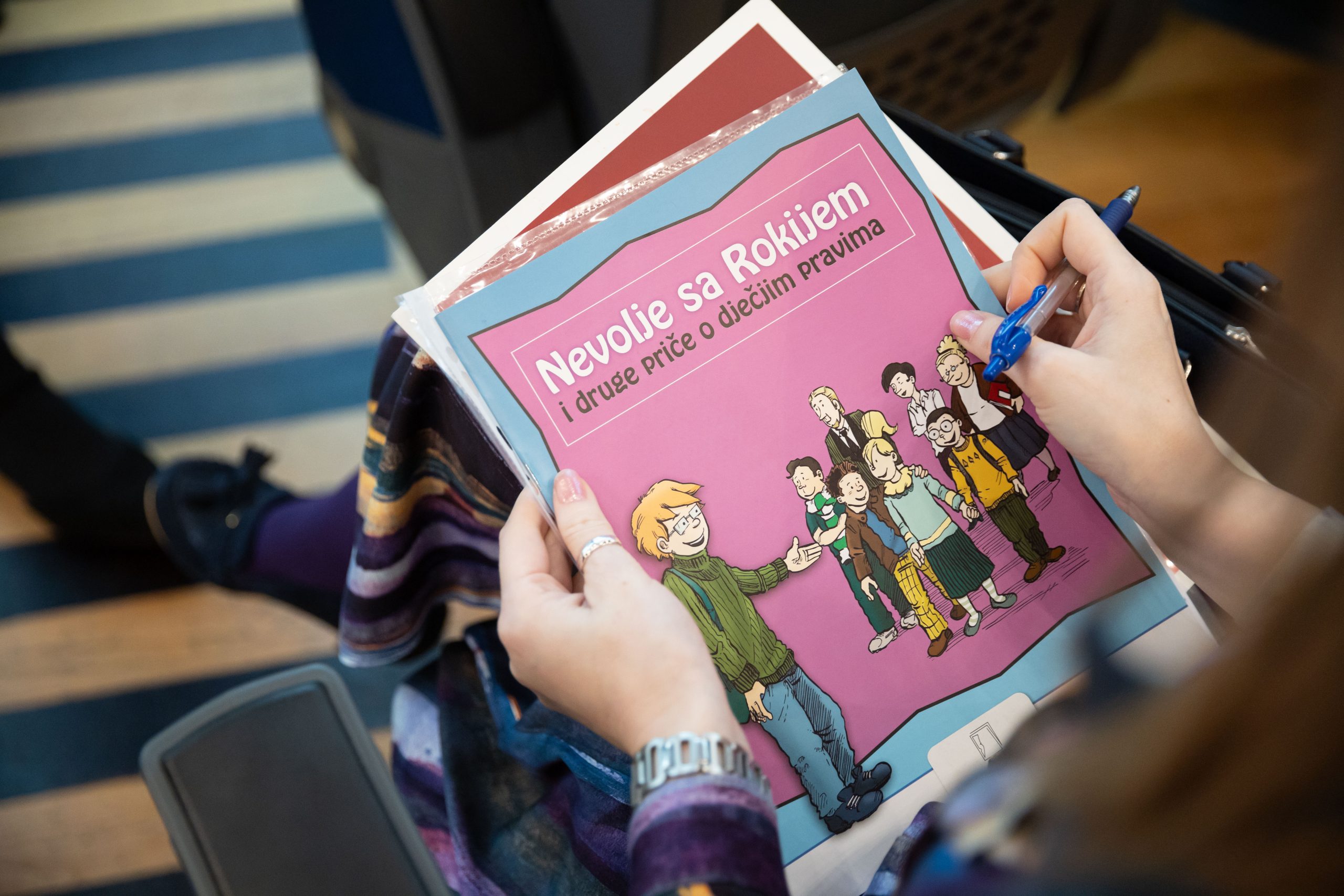

29/02/2024Children’s Right to Human Rights Education in Montenegro: The Subject of Civic Education Should Once Again be Made Compulsory

“Since 2017, civic education has not been a mandatory, but rather an optional subject in schools, as if life in a civil society is a matter of choice and not a constitutional obligation of all of us”, said the director of the Human Rights Action (HRA) Tea Gorjanc Prelević at the meeting that was organised today in the Cultural Information Centre “Budo Tomović” on the topic of “Children’s Right to Be Educated on Human Rights in Montenegro”.

The documentary film “For a Civic Future”, created by Nemanja Živaljević and produced by HRA, was also promoted at the meeting. It was created as part of the project “Education of young people and children as a way of reducing hatred and violence”, supported by the Embassy of Canada through the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives.

“Yesterday, I was with parents who had lost their children in war crimes, and I watched them caress their names engraved on headstones. Then I opened the news portals and read the statements of parents of children who were killed in the massacre at the elementary school in Belgrade, and now I am looking at the overview of last month’s cases of severe peer violence that took place in Podgorica alone. We have not done enough to prevent violence, and it was not the right time to reduce civic education to the level of an optional school subject”, said the director of HRA.

She added that everyone has the right to learn and practice tolerance, empathy and respect for diversity from an early age, and how to resolve conflicts without violence, and that the initiative to re-introduce civic education as a compulsory subject in schools can help make it possible.

HRA, ANIMA and the Centre for Civic Education submitted to the Minister of Education, Science and Innovation, Prof. Dr. Andjela Jakšić Stojanović (PES) the initiative for bringing back the subject of civic education as compulsory in primary and secondary schools in Montenegro. It is currently an optional subject.

“Civic education used to be a compulsory subject in primary schools for 13 years, and in secondary schools for 10, until it was demoted to the level of an optional subject in 2017 as a result of the reform thatw as implemented by the then Minister Damir Šehović”, reminded Gorjanc Prelević.

At the HRA meeting, Minister Jakšić Stojanović said that she supports the initiative to introduce civic education as a compulsory subject. “We launched an initiative to analyse and reform the programme plan. We are taking into account comparative practices, but also the context in which our educational process is being implemented”. She mentioned the example of Estonia as a good example for Montenegro.

“We will also consider the introduction of other subjects, such as media literacy, rhetoric, programming, entrepreneurship, logic, ethics…”, said the Minister.

Deputy Head of Mission of the Canadian Embassy in Belgrade, David Morgan, pointed out that teaching children about human rights encourages them to stand up against injustice, to be responsible and empathetic, and to want to prevent violence: “It is our duty to provide this to children”.

The author of the film, journalist Nemanja Živaljević, said that it was while making the documentary that he understood the challenges the children are faced with, but that he also realised where we have failed as a society.

“We have to change the system, whose very foundation is the education system. The introduction of civic education in schools would lead to independent, tolerant and critical children”, pointed out Živaljević.

The film “For a Civic Future”, which was shown at the Cultural Information Centre “Budo Tomović”, talks – among other things – about the need to return civic education as a compulsory subject in schools, showing children and adults talking about how much we are missing this type of education in Montenegro.

Almost all those who participated at the meeting agreed that civic education should be a mandatory part of regular education, but they added a few other observations as well.

Deputy Ombudsman Snežana Mijušković said that we are lacking quite a lot in education, that we do not have enough pedagogical and psychological services in schools, and that there is no institutional memory. “The fact that we have been talking about all these issues for years is tragic. We shift the responsibility amongst us, and there is no progress”, she pointed out. “We often treat children as pure décor because we don’t have time to hear them out.”

Psychologist Ana Ćalov Prelević, who has many years of experience working in elementary schools, pointed out that the latest positive change is that children themselves are asking for help, adding that they and their parents also often need therapeutic support outside of school. “Research has shown that our children lack tolerance, and that they have even less interest in school than we think”.

Kristina Mihailović from the “Parents” association said that we are experiencing a crisis within families, and that we do not have support systems that could help them. She also pointed out that we are greatly mistaken when we say that the problem is that children have too many rights, “because when we say that, we mean that we do not have the right to physically punish them when they make a mistake”.

“Children in Montenegro do not have too many rights, those that are referred to in international documents – regarding education, health, safety… No one says that children are allowed to do whatever they want”, said Mihailović.

Marija Gošović from the Ministry of Education added that parents are the key partners in education reform, and that “school is the ideal testing ground for the application of children’s rights”. She also pointed out that children “know very well how to recognise problems and give suggestions on how to solve them”.

Nadja Durković from the Textbook Institute and Olivera Nikolić from the Media Institute pointed out that media literacy, which was recently introduced as an optional subject in schools, is equally important as civic education. “Media literacy and civic education are a good way to introduce an approach to the education system that encourages critical thinking, cooperation, communication and creativity. Those subjects should be assigned to the most creative teachers, those who live in line with civic values, believe in change, and are ready to learn from young people”, said Nikolić.

She said that the system should recognise, encourage and foster such an approach of teachers, instead of “pouring cold water on their enthusiasm”.

Durković said that children lack spiritual breadth provided by reading appropriate literature. She cited the publication of Eugenio Carmi and Umberto Ecco, “Three Stories”, as an example of a book that is accessible for children, unlike some of the books from the assigned reading list that go right over their heads.

Anita Marić from the Bureau for Education Services added that it is important to think strategically so as to avoid superficiality: “When we ourselves are powerless, we tend to accuse others. If a system existed, and if parents weren’t discouraged, they would behave differently”, said Marić.

Demir Ličina, Juvenile Delinquency Inspector, and Andjela Ivanović from the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare, also emphasised the role of the media, saying that they must be careful how they write about these topics so as not to endanger the rights of minors and not make it more difficult to solve the problem.

School principals Tatjana Damjanović and Ljubo Ćeranić supported the re-introduction of civic education as a compulsory subject, but they also warned that schools do not have a sufficient number of properly educated staff.

“If civic education is to be introduced as a compulsory subject, we must organise new trainings for the teaching staff. We should select teachers who are already familiar with these issues; we don’t want them to go to the courses just so to meet the norm”, concluded Damjanović.

Photographer: Filip Roganović

- Tea Gorjanc-Prelević, executive director of the NGO Human Rights Action

- Anđela Jakšić Stojanović, Minister of Education, Science and Innovation

- David Morgan, Political Counsellor and Deputy Head of Mission of the Embassy of Canada in Belgrade

- Nemanja Živaljević, film author, journalist and editor

- Marija Gošović, Director of the Directorate for General High School and Vocational Education in the Ministry of Education, Science and Innovation

- Snežana Mijušković, Deputy Protector of Human Rights and Freedoms of Montenegro

- Ana Ćalov Prelevic, psychologist

- Kristina Mihailović, executive director of the NGO “Parents”

- Tatjana Damjanović, director of “Marko Miljanov” elementary school in Bijelo Polje

- Ljubo Ćeranić, director of the elementary school “Sutjeska” in Podgorica

- Anđela Jakšić Stojanović, Minister of Education, Science and Innovation

- Aleksandra Hajduković, director of the Institute for Textbooks and Teaching Aids (left) and Nađa Durković, editor of the Institute for Textbooks and Teaching Aids (right)

- Anđela Žarić, NGO Prima

- Anita Marić, consultant for inclusive education at the Institute for Education

- Demir Ličina, police inspector for combating juvenile delinquency and domestic violence at the Security Center in Bijelo Polje

- Anđela Ivanović, representative of the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare

- Aet Salh, representative of the Secretariat for Social Welfare of the Capital City

- Olivera Nikolić, NGO Institut za medije

- Dragana Đurica, parent

- Milena Brajović, NGO Centre for Civic Education

- Marija Gošović, Director of the Directorate for General High School and Vocational Education in the Ministry of Education, Science and Innovation (left) and Jelena Borovinić Bojović, President of the Capital City Assembly

- Participants in the film: Pavle Petrović Njegoš (left) and Luka Đurica (right)

English

English